Hit enter to search or ESC to close

Features

INSIDE MUSIC

Defining the qualities of a good, bad or indifferent musical instrument is tricky, particularly because its sound/tone is so dependent on the player’s skill – superior breath control, finesse with the bow, accurate, agile fingers and a dexterous embouchure all make a difference.

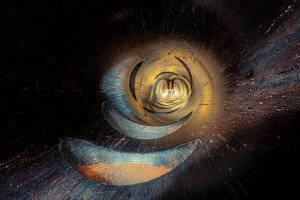

The interior of a Hopf violin - circa 1880

And while a piece of music might be described as ‘bewitching’, the term covers an awfully broad spectrum. As Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw once caustically wrote, “hell is full of musical amateurs.”

But what, exactly, constitutes a well-made, beautifully constructed instrument which – in a master’s hands – produces ‘heavenly’ music? Trying to answer that is fruitless – it’s intangible, an elusive quest. But New Zealand photographer Charles Brooks offers a clue.

Inside a 1995 Low C Prestige Bass Clarinet

Using specialist probe lenses and complex imaging techniques, Brooks’ striking photos reveal the hidden details inside musical instruments. Each photo is a blend of hundreds of frames. The sharpness and detail renders these spaces as vast rooms, exposing the tool marks of the makers, repairs carried out through the centuries, and the hidden architecture within.

The images form part of Brooks’ Architecture in Music series and feature rare instruments with fascinating histories: A cello once hit by a train, a didgeridoo hollowed out by termites, an exquisite Fazioli grand piano hand-made from 11,000 individual parts.

With this unusual photography and perspective, a 240-year-old cello looks like the inside of an ancient ship, a century old saxophone becomes a gaping tunnel of green and gold, the keys of a piano become a monolithic temple.

A cellist since childhood, Brooks has played with some of the world's great orchestras and turned to full time photography in 2016.

A Fazioli Grand Piano

The Architecture in Music series will have its first major international exhibition in 2024 and will run for six months at the Napa Valley Museum as part of the Napa Valley Festival. Smaller exhibitions will also be held in Budapest and Stockholm.

Visit https://www.charlesbrooks.info/ to view more of the images.

For more information call +64 27 203 2269 or email: Email: photos@charlesbrooks.info

Every orchestral player believes his/her instrument is special – but few instruments in the PSO can rival the life experiences of Sharyn Palmer’s viola, which in 2024 celebrated its 291st birthday.

Peering through the viola’s f-holes reveals a label bearing the name Franciscus de Emilianis fecit Rome Anno Dni – with the date of manufacture – 1733.

A Google search reveals that Emilianis (his name is sometimes spelt Francesca Emiliani) was one of the most highly-regarded Italian luthiers of the period. He was born in Bologna (c. 1680 – 1736) but it seems he worked mainly in Milan and Rome.

His creations (mostly violins but also violas and cellos) are coveted and the archives of most mainstream auction houses are sprinkled with instruments carrying his name. It’s believed he was a disciple of two of the most well-known German luthiers of the period – Jacob Stainer and David Tecchler – and modelled his work around their instruments.

Stainer (c. 1618–1683) is often cited as the ‘father’ of German violinmaking, while Tecchler (1666–1748) is best-known for his cellos and double basses.

According to the background notes of the various auction houses, Emiliani’s craftsmanship is such that his instruments have sometimes been mistaken as the work of more famous masters. He was particularly well-known for the quality of his varnish.

Sharyn’s viola – unsurprisingly – carries a few battle scars sustained over the centuries. A careful examination shows that the scroll has been replaced (the date of this modification is unknown). There is also evidence of cracks that have been repaired.

She bought the viola in her first year of university (1964). She spotted it in the shop of Auckland luthier Norman Smith and bought it for £65 – the sum total of her savings earned from part-time work teaching violin at Bayswater Intermediate Music School.

Her viola teacher at the time was Felix Millar (a founding member of the National Orchestra before it became the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra). He wasn’t particularly impressed with the viola and said ‘it would have to do until we could find a better instrument.’

“But it’s always satisfied my needs,” says Sharyn. “No one else enjoys playing it very much but I’ve adapted to it. I don’t know why, but violas vary considerably in size.

"This one is quite small and it’s a little weak on the lower two strings. Still, it has a lovely tone and I’ve never had problems when playing for extended periods.”

As with many ancient instruments, the viola’s precise provenance is sketchy. Sharyn admits there is some doubt about the heritage. “One expert who examined it didn’t believe the viola was ‘good enough’ for the Emilianis label.

“But I took it to a valuer from Brompton’s earlier this year and he was keen to buy it – saying it was definitely pre-1750 and he was confident it was made in Milan, not Rome. He said it was probably worth about $40,000.”

Brompton’s Auctioneers is a London-based company specialising in fine and rare instruments. Representatives visit various parts of the world every year, scouting for desirable instruments.

Whatever the true history of viola, there’s no denying its antiquity. More importantly, in Sharyn’s expert hands it projects a gorgeous sound, and the PSO musicians are very happy to have it in their midst.