Hit enter to search or ESC to close

Echoes from a Lost Era

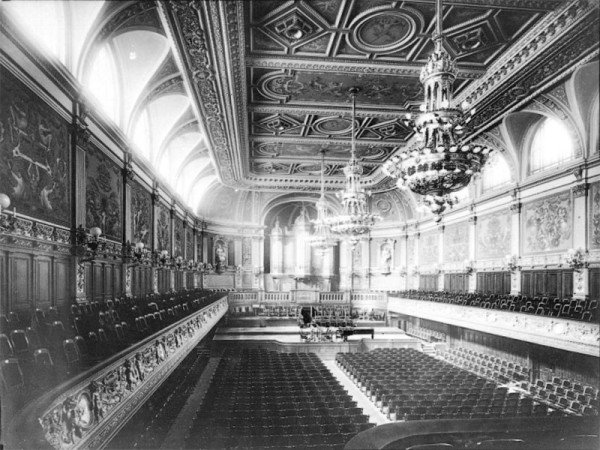

The Grand Hall in Auckland's Town Hall. Its design was modelled on the Neues Gewandhaus in Leipzig.

Many of Europe’s most famous concert halls were severely damaged (or destroyed) during WW2. A few were faithfully restored; others were replaced with more modern edifices – their true heritage consigned to rubble. Auckland’s Grand Hall is a living reminder of the lost elegance.

The Grand Hall – in the city’s Town Hall – is home to Auckland’s Philharmonia Orchestra – and internationally-renowned for its fine acoustic. And that’s not entirely surprising, given that it was modelled on Leipzig’s Neues Gewandhaus – one of the world’s finest concert halls in the late 19th century.

Opened in 1911, the Grand Hall is a classic example of the ‘shoe-box’ design evident in many of Europe’s pre-WW2 concert halls. Understanding and defining a superior acoustic is an elusive exercise – but it is thought the dimensional ratios and geometry of the shoe-box design (1:1:2) proved to be a crucial starting point. Effectively, a space twice as long as it is wide and high.

Engineers today base concert hall designs on screeds of sophisticated acoustic data – research tools they didn’t have when the Neues Gewandhaus was built in 1884. How Martin Gropius (the architect/designer) stumbled across the sublime shoe-box ratio is sometimes attributed to divine intervention, intuition – or pure luck. Whatever it was, he struck gold.

The Neues Gewandhaus pre-war. It was destroyed by Allied bombing raids in 1943/44.

The hall quickly established an international reputation for its acoustic, attracting the best composers and conductors. So much so that younger architects freely incorporated its dimensional and geometric features into their designs.

Among the edifices that benefitted were the Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam (opened 1888), the Boston Symphony Hall (1900) and Auckland’s Grand Hall (1911). The Grand Hall, in particular, bears a striking resemblance to the Leipzig masterpiece.

Orchestras and concertgoers throughout the world were very fortunate that the Gewandhaus’ acoustic formulae were shared: Allied bombers obliterated the hall in 1943/44. Leipzig only received a more modern replacement (a significant departure from Gropius’ design) in 1968. It too, is noted for its acoustic excellence – though it’s fair to say ‘divine intervention, intuition or luck’ played less of a role in its creation.

The European concert halls that did escape the WW2 carnage were very lucky – aerial bombing, after all, was a relatively new development and accuracy was largely a ‘hit-or-miss’ affair. The unfortunates on the ‘hit’ list included concert halls in Leipzig, Dresden, Berlin, Hamburg, Vienna, Warsaw, Budapest, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Milan – as well as in Britain.

Among the UK’s major losses was the Queens Hall in London – the premier pre-war venue and home of the BBC Symphony and London Philharmonic Orchestras. A single incendiary bomb in May 1941 gutted it. But the nearby Royal Albert Hall, with its iconic circular domed roof, was spared: it’s sometimes suggested it escaped serious damage because pilots (on both sides) found it a useful navigational aid.

Coventry wasn’t so lucky – and there was some irony in the Luftwaffe’s bombing campaign. In November 1940 the city was devastated by a heavy attack codenamed ‘Moonlight Sonata’ by the Germans. Surely Beethoven wouldn’t have approved?

Auckland’s Town Hall (designed by Melbourne-based father-and-son architects J.J. & H.J. Clarke) carries the New Zealand Historic Places Trust’s 'A' Classification – a “building having such historical significance or architectural quality that its permanent presentation is regarded as essential.”

Indeed – and a visit to an APO concert in the Grand Hall underscores the point.